Memoir vs. Fiction

Lehrer adds his own dose of ambiguity to a question frequently examined in literature: where is the line between fiction and non-fiction? This question has been posed in many different ways over the years; 2003 saw the publication of A Million Little Pieces, authored by the poster boy for the Memoir vs. Fiction debate, James Frey. His harrowing tale of crack addiction followed by rehab and redemption became a huge hit after Oprah chose it for her book club and Frey appeared on the show. Oops. It turned out the book was totally fabricated and Frey had to apologize – and even worse – caused Oprah to apologize to her legion viewers. It was the publishing scandal of the decade, and the debate still rages on:

“Memoir writing is cheating,” wrote Taylor Antrim in his 2010 Daily Beast article, Why Some Memoirs Are Better as Fiction. “I’ve always believed this, even before l’affaire Frey, before fact-checking purportedly true tales of lives lived became a contact sport. And, anyway, by cheating I don’t mean exaggerating the truth. Of course memoirs contain misrepresentations, even outright lies. Has anyone ever told a story about themselves without fibbing a little? (A good story, that is.) Lemon’s book (Happy, Scribner, 2009) is full of decade-old dialogue; the guy wasn’t toting a tape recorder in 1997. He’s making it up. Relying on his memory, and memory is a liar. (I’ve never, by the way, bought that story about why Truman Capote never took notes during interviews for In Cold Blood. Supposedly he had a photographic memory. I say Capote didn’t want to be tied to a transcript. He wanted to tell a story.)”

Here are two other articles on the topic:

Truth or Lie: Fiction vs. Memoir - How Memoir Writers Can Approach Truth and Healing

Linda Joy Myers, FreelanceWriting.com

10 Ways to Tell if Your Story Should be a Memoir or a Novel

Adair Lara, Writer's Digest

Feature

An Interview with Award-Winning Author Warren Lehrer

Part 1 of 2

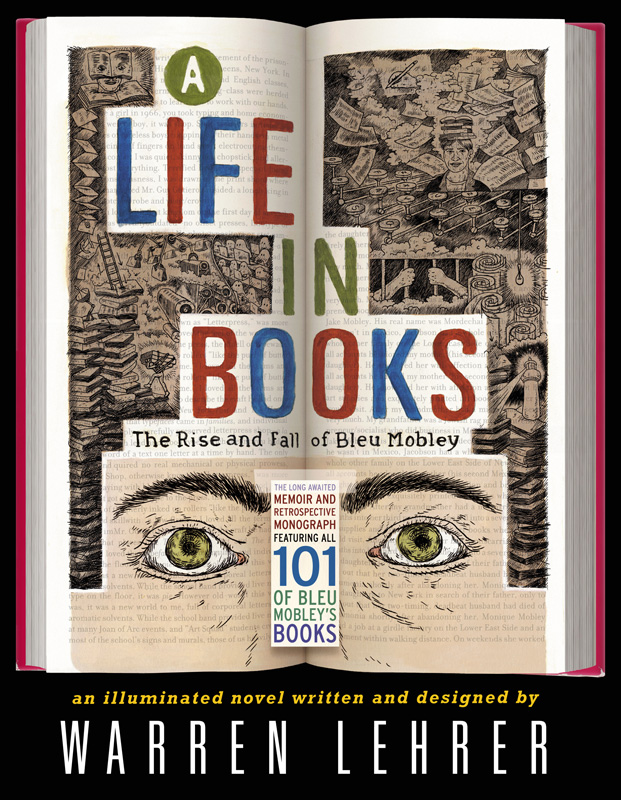

IP got the chance to speak with award-winning author Warren Lehrer about his incredibly unique novel, A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley (Goff Books), which follows the career of fictional author Bleu Mobley all the way through youth to success, fame, and eventual downfall.

With A Life in Books, Lehrer has upended the modern novel form and its narrative limitations, creating a rich and engaging story through visual literature. In the first of a two-part interview, Lehrer gives us insight into the creative journey that led to Bleu Mobley, a character who captures so many of the complexities inherent in choosing writing as a career.

Tell us about your background and your past experience with publishing.

I was a painting and printmaking major in college. On the side I wrote music and theater reviews for the school newspaper, and poetry and short stories for myself. One day I brought a stack of secret drawings to a painting teacher of mine. The intricate, puzzle-like drawings combined abstract marks, shading, letterforms and words. Leafing through the stack, my teacher shook his head and wagged his finger in my face. “You’re a good student, Warren, but you’re barking up the wrong tree here. Words and pictures are two different languages. They operate from completely different parts of the brain, and shouldn’t be combined.”

I left his office feeling like I’d been given a mission in life. And for better or worse I’ve been combining writing and picture-making ever since.

I went on to get a masters degree in graphic design so I could learn the tools and methodologies needed to compose and produce my own books and multimedia projects. I say compose my own books because I was very influenced by music and music notation, and also because I printed my first books in a letterpress shop (a la Gutenberg) using a composing stick—that metal tray you hold in one hand as you pluck alphanumeric characters from a case of type with the other. Within a year, my book-composing machinery evolved five centuries to phototypesetting and offset printing. My thesis (from the Yale School of Art + Architecture) was my first offset printed book, a performance score called versations: a setting for eight conversations inspired by some very colorful people I’d come to know on Venice Beach during the summer of 1979.

A page spread from Warren Lehrer and Dennis Bernstein’s 1984 book/play French Fries, from a section in which each character imagines a book they might one day write. A foreshadowing of A Life In Books.

With versations and my next book i mean you know (Visual Studies Workshop, 1983), I developed an approach that attempted to capture the patterns of speech and the shape of thought on the printed page. Each character was set in a different typeface and typographic configuration. Pauses and silences were indicated by blank space or line breaks (as in verse). Sometimes multiple conversations appeared on a single page. In the book/play, French Fries (VSW, 1984), co-authored with Dennis Bernstein, I used images, symbols, and color as well as typography to evoke the greasy comfort of a fast food restaurant and the entangled aspirations of the characters who inhabit it.

What led to the creation of A Life in Books?

These early books gained attention in the somewhat rarified worlds of book arts, experimental literature, and graphic design, but I came to realize that some of my biggest fans hadn’t actually read my books cover to cover. As the writer in me started to care more deeply about the stories I was telling and the characters I was portraying, my approach to the visual composition, while still expressive, became more mindful of the reader.

In The Portrait Series (four book suite, Bay Press, 1995), I set out to portray American eccentrics—off the cuff bards, stoop philosophers, and sit-down comedians who straddle the wobbly line between brilliance and madness.

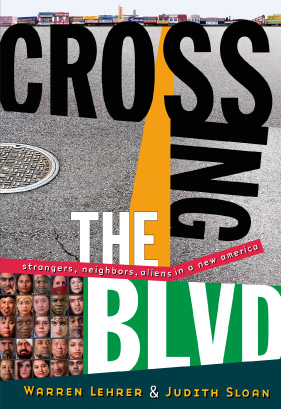

My last book, Crossing the BLVD: strangers, neighbors, aliens in a New America, (W.W. Norton, 2003), written with Judith Sloan, documents and portrays the stories and images of 79 new immigrants and refugees from all over the world who live in Queens, NY. The four color, 400 page book was part of a multimedia project that included public radio documentaries, a performance, an interactive website, a mobile story booth, an audio CD, and an exhibition that traveled to 15 sites throughout the United States.

After representing all these real people and their stories, I felt a need to work on something that gave me more room for invention, and allowed me to get at the interior world of characters. I started looking at all these book ideas I had scratched into notebooks through the years, and drawers full of short stories and interior narratives I had written. And somehow, this peculiar, well-meaning (if ethically challenged) writer character emerged—Bleu Mobley—who was in prison looking back on his life and career.

I guess I got so inside this character, I didn’t only write his story, I created his entire bibliography.

Bleu encompasses many different variants of the author over the course of his career: journalist, novelist, professor, bestselling-author, and finally a prisoner locked away because of the consequences of his writing. What drives him from one stage to the next?

Bleu Mobley’s life in books begins by accident, really, in the basement print shop of the Joan of Arc Junior High, where he is tracked—as terminally working class—to learn how to work with his hands. He ends up falling in love with that shop and everything that has to do with letters, ink, paper, and books. The shop teacher, a former newspaper man, teaches Bleu the secrets of the news trade from setting type to the tenets of good journalism, and charges him and the other self selected print shop geeks with putting out the school newspaper.

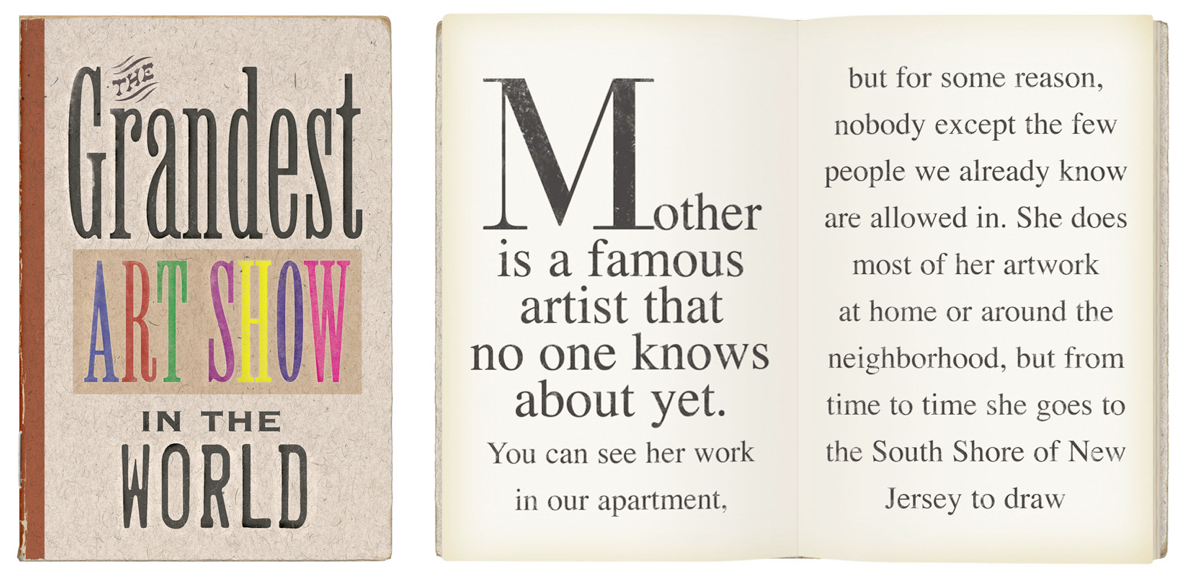

At fourteen, Bleu becomes a muckraking reporter for the school rag, and also composes his first book, about a magical experience he had one day with his manic depressive artist mother at a marshland in New Jersey.

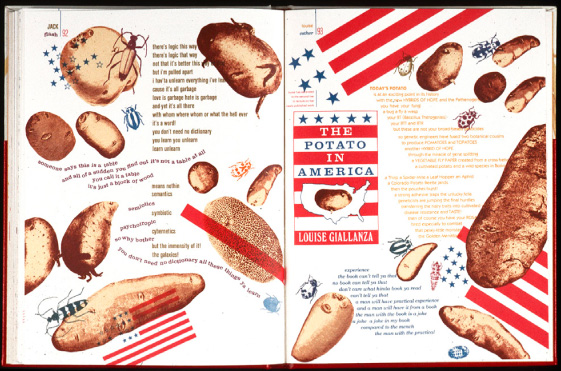

The cover and first page spread from Bleu Mobley’s first hand-printed book, circa 1967, from Lehrer's novel A Life in Books.

Bleu never had a father, and his mother never told him who he was, but Bleu’s Aunt Chloe, who had a few too many gin and tonics one night, told Bleu that his father was a very famous man, who was madly in love with his mother, but because of his fame and his having a family of his own, had to cut off the relationship. So Bleu let his fantasies run wild in a series of books he called My Famous Fathers bound in a bifurcated dos a dos binding. On one side of each book he described what each of his hypothetical Famous Fathers did to transform the world. The other side portrayed the kind of relationship that particular famous father might have had with Bleu had he chosen to follow his passion with responsibility.

In the Grandest Art Show and Famous Fathers, you have the basis of Bleu’s creative output for the rest of his life, fluctuating between reportage, and making up stories. With one, he is a witness, trying to make sense of the world around him. With the other, he transforms loss into art.

In the Grandest Art Show and Famous Fathers, you have the basis of Bleu’s creative output for the rest of his life, fluctuating between reportage, and making up stories. With one, he is a witness, trying to make sense of the world around him. With the other, he transforms loss into art.

A Life In Books pairs Bleu’s reluctant memoir—as whispered into a microcassette recorder from the darkness of his prison cell—with a retrospective monograph of his life’s work represented by all 101 of his book covers, original catalogue descriptions, and many book excerpts that read like short stories.

For years Bleu claimed to have never written about himself, yet we discover him and the people he loves sluicing through almost all his books, however obliquely. That gap between those two realms is the mysterious part for me, and for the reader, because the relationship between the events and people in Bleu’s life and the events and characters in his books are hardly ever one to one.

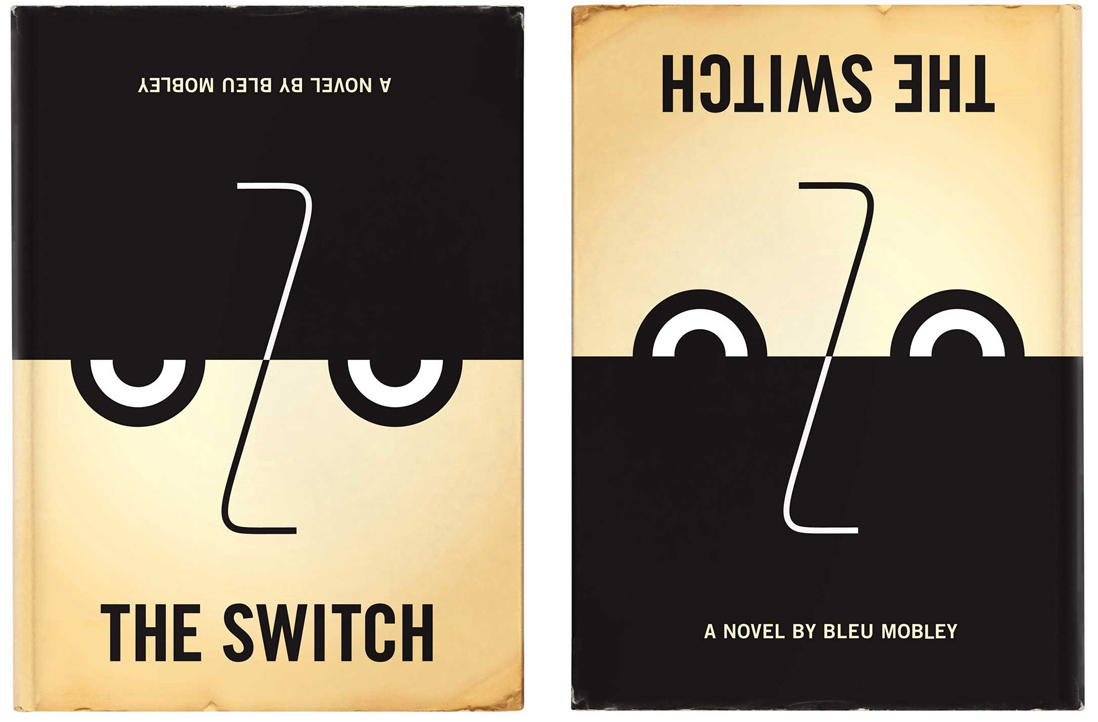

Up and down views of the palindromic cover of Bleu’s first novel The Switch, circa 1979, from A Life In Books.

When he comes home after a two-year stint as a foreign correspondent reporting on wars and violent conflicts on the West Bank, El Salvador, and then Haiti, he writes his first novel about a day on earth when everyone is switched with their number one nemesis. It’s not until five years later that he writes a book based on people and situations he witnessed in Haiti, but that book also has a lot to do with things that were going on in his marriage at the time he was writing the book. The transmigration of life into art transcends gender, geography, and chronological time. The chart I used to diagram the events in Bleu’s life, what was going on in America and the world at those times, and his bibliographic timeline was in continual state of revision.

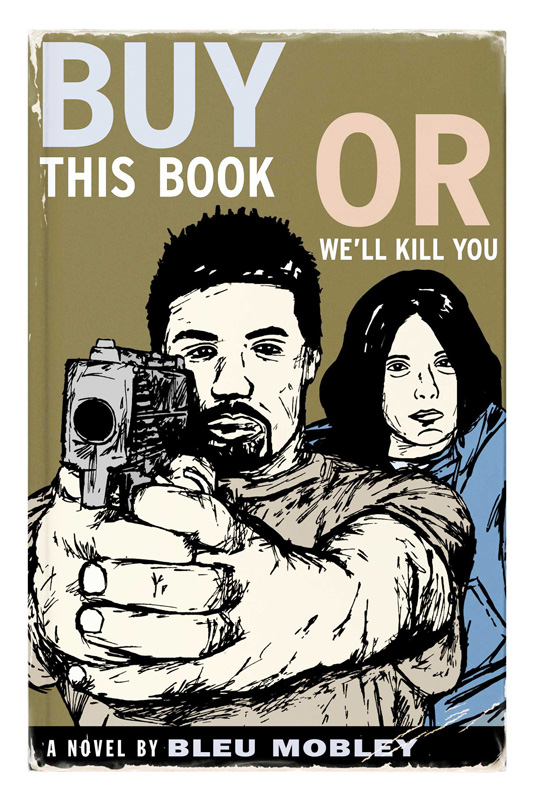

As life poses new challenges and opportunities, Bleu’s goals change. He never aspired to write a bestseller. If it weren’t for an independent filmmaker making a film out of it, his novel, Buy This Book Or We’ll Kill YOU, would most likely have fallen to the obscure fate of his previous books. The movie, which bore very little resemblance to the book, became a blockbuster, and on the coat-tails of the hit movie, Bleu’s book became a bestseller. The first of many.

As life poses new challenges and opportunities, Bleu’s goals change. He never aspired to write a bestseller. If it weren’t for an independent filmmaker making a film out of it, his novel, Buy This Book Or We’ll Kill YOU, would most likely have fallen to the obscure fate of his previous books. The movie, which bore very little resemblance to the book, became a blockbuster, and on the coat-tails of the hit movie, Bleu’s book became a bestseller. The first of many.

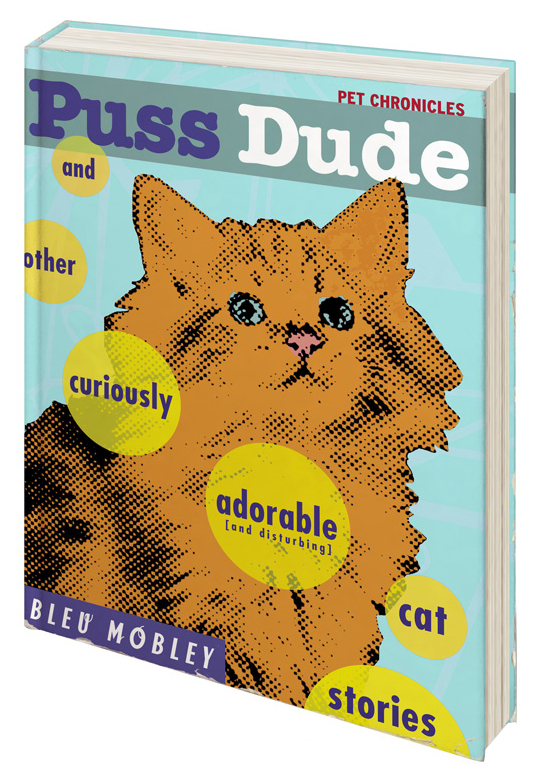

Bleu detested genre writing, but after his daughter was struck with a life threatening illness, he needed serious money to make sure she could get the best health care in the world. He began writing murder mysteries, self help books (under the name Dr. Sky Jacobs), and even cat books.

And yes, Bleu’s writing does land him in prison. The very thing that was his oxygen, his fix, his wings, his armor and fortress, and his bread and butter became the cause of his demise.

How do you think each transition in Bleu’s personal journey speaks to the relationship between a writer’s life and his/her work?

I was interested in exploring the creative process of an artist—beyond it being some kind of natural or supernatural phenomena that bursts forth or strikes from on high. I do get into the inner workings of how Bleu writes his books and how his various writing machines (from the composing stick of his junior high school letterpress shop to his factory of writing assistants) influence his writing. But the larger reveal in this book is—how life creates the artist; how life influences an artist’s creative output, and vice versa; how one door opened or closed, one comment from a teacher, diagnosis from a doctor, encounter with a stranger, one situation leads to another without a plan or a map, and a life writes itself. And if you happen to be a writer, you can’t help but write about the lives around you, and the life of your times. You try to fill in the holes, connect the dots, make whole that which is broken, and make sense of that which seems senseless.

A Life in Books unabashedly explores the relationship between narrator and reader, setting up the novel in such a lifelike way that “fiction” seems an inadequate descriptor. How did you create such a realistic character?

In the note from the editor in the front of A Life In Books, I, Warren Lehrer, tell the reader that I first became aware of the Bleu Mobley prison tapes from a People Magazine article about the bestselling author’s ongoing legal battles. The article briefly mentions Bleu having started and then aborted writing a memoir in prison. “According to a source close to the author ‘Mobley began making notes for his tell-all apologia by whispering into a tape recorder during sleepless nights.’”

I go on to say that I was surprised Bleu let me listen to the tapes, since we were mere acquaintances, and I was even more surprised that he agreed to my doing a book on him (based largely on the tapes).

After the editor’s note, I step aside, and present evidence of Bleu Mobley, the man and his books, side by side, with no narration or commentary from me. It’s up to each reader to hunt for where the truth lies (so to speak). Is it more in the tell-all confessional Bleu whispers into a tape recorder from his prison cell, or more in his fictions, or in his non-fictions? Is he an important man of letters or a sell-out? A champion of the voiceless or an elitist hypocrite? The conscience of America or an ungrateful traitor? And is his story a parable of the rise and fall of a culture, or a swan song for the book itself as a medium?

After the editor’s note, I step aside, and present evidence of Bleu Mobley, the man and his books, side by side, with no narration or commentary from me. It’s up to each reader to hunt for where the truth lies (so to speak). Is it more in the tell-all confessional Bleu whispers into a tape recorder from his prison cell, or more in his fictions, or in his non-fictions? Is he an important man of letters or a sell-out? A champion of the voiceless or an elitist hypocrite? The conscience of America or an ungrateful traitor? And is his story a parable of the rise and fall of a culture, or a swan song for the book itself as a medium?

Soon after A Life In Books was published, I started getting questions from readers, and people who come to my performance/readings, asking if Bleu is still in prison, is he writing again, is he alive? When I say that he’s made up, that it’s all a fiction, people seem to be in shock. I’m not trying to fool anyone—it says right on the cover that it’s a novel, and on the copyright page it says, This is a work of fiction, etc...

I gather there is a verisimilitude to Bleu’s voice, and to the excerpts, and the whole documentary feel of the thing, the 3-D renderings of the books and how tattered some of them look. Now, whenever I do a live presentation, I make sure that the person introducing me says that A Life In Books is a novel, and I project the cover, which plainly says that this is a novel. It doesn’t seem to matter. The first question in the Q&A, invariably, is about the whereabouts of Bleu Mobley. I’ve decided to take it as a compliment. After all, when you read a novel, you want to suspend your disbelief.

The novel also explores the fragile and often blurry line that distinguishes truth and fiction in a story. How does your book reflect on methods of storytelling in general, and the novel in particular?

It’s funny because the blurring of the lines between truth, myth, and fiction is a theme that runs through the whole novel. The name Mobley, we find out early on, came from an alias that his Jewish rag merchant grandfather made up for his travels outside New York. His real name was Mordechai Jacobson, who had family on the Lower East Side, and a secret family in Mexico City under the name Jake Mobley. Bleu never met his grandfather but he found out that he was a mesmerizing raconteur whose stories turned out to be more theater than reality.

The very definition of the terms fiction and non-fiction perplexes the young Bleu Mobley once he becomes an author and is asked to make these distinctions. He asks his teacher,“If non-fiction is the truth, why is it defined in the negative? Wouldn’t it make more sense to call true stories just that—true stories—and call novels and other made-up stories non-true stories?” He wonders what kind of world allows truth to play second fiddle to fiction? Of course he goes on to discover how fiction can allow you to get at the truth in a different kind of way.

Early in his career Bleu writes The Book of Lies based on his neighbor and best friend, an atheist and self-confessed liar who swears he’s telling the truth and nothing but the truth so help him God. His friend refuses to let him use his real name, so Bleu changes all the names in the book, and subtitles it “a true fiction.”

Years later, Bleu starts writing a novel about a right-wing think-tanker who espouses the privatization of just about everything, and also happens to be a very loving family man. Halfway through the first draft, the voice of the protagonist—Blane Masters—becomes so palpable to him, he scraps the novel and makes Masters the author of his own book.

Bleu goes on to hire an actor to play Masters on a book tour, do interviews and debates. He describes the idea to his head writing assistant as an experiment in living fiction. “Instead of writing characters and trapping them in a book, what if we play them out in three dimensions, see how they react to different situations? Let’s face it, Monica, the old-fashioned novel is an endangered species. Creating fictional characters who speak for themselves and interact with others might be the novel of the future.”

Bleu goes on to hire an actor to play Masters on a book tour, do interviews and debates. He describes the idea to his head writing assistant as an experiment in living fiction. “Instead of writing characters and trapping them in a book, what if we play them out in three dimensions, see how they react to different situations? Let’s face it, Monica, the old-fashioned novel is an endangered species. Creating fictional characters who speak for themselves and interact with others might be the novel of the future.”

Bleu is in a federal detention center for refusing to reveal the name of a confidential source of a non-fiction book he wrote about the president of the United States (43). He remains mum for nine months, until he can no longer take being away from his wife and kids. The truth should set him free. The only problem is, the truth will also disgrace him. He decides to tell the grand jury only what they need to know, but he owes his readers, and his colleagues, friends, and family a lot more than rumors of a reluctant confession.

Like Schehezade, Bleu tells his story as a means of survival. My use of the number 101 is, in part, a play on all those 101 Best this and that books. More so, it’s a nod to 1001 Arabian Nights—the ultimate collection of stories nested between the covers of one book. Scheherazade kept telling stories in order to survive, which is true of Bleu Mobley, and probably most writers.

* * * * * *

Be sure to read Part 2 of IP’s interview with Warren Lehrer. You can purchase A Life in Books through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Indie Bound, or Goff Books.

Lauren White recently graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in History and English. She is serving as assistant editor at Independent Publisher and hopes to continue her career in publishing in New York City. Please email her at larenee [at] umich.edu with any questions and comments.

Lauren White recently graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in History and English. She is serving as assistant editor at Independent Publisher and hopes to continue her career in publishing in New York City. Please email her at larenee [at] umich.edu with any questions and comments.